If you still have and read a print Bible (something increasingly less common), then you’ve seen those title pages that indicate “Old Testament” and “New Testament.” Even the digital versions of the Bible have these indicators, but you probably don’t ever navigate to the “New Testament.” You’re usually looking for “John 3” or searching for some passage that contains the few words you can remember.

Since these titles are not original to the text of Scripture, where did they come from? What do they mean? And how do these title pages inform our understanding and interpretation of Scripture?

The first known division of the two biblical Testaments was by a theologian and pastor in the late 2nd century, named Melito of Sardis. Melito listed 38 of the same 39 books we have today, with the only exception being the book of Esther, which he may have counted as part of one of the other books he listed.[1]

At any rate, Melito didn’t call the Old Testament the Old Testament… Instead, he called it the “παλαια διαθήκη” (or palaia diathākā), which is Greek for Old Covenant. But Greek is a precise language, and at least two words might be translated as covenant. One is “διαθήκη” (or diathākā) and the other is “συνθήκη” (or synthākā).

Unless you’re interested in studying Greek, knowing or remembering these words isn’t that important, but the distinction between the two is important.

συνθήκη (or synthākā) means something like a contract or agreement, allowing for and even expecting equality among the participants.

διαθήκη (or diathākā) conveys the idea of a final will or testament, emphasizing a unilateral or lop-sided contract, where there’s a great benefactor and a lesser beneficiary.

Most of us know what a final will and testament is because we’ve had to deal with settling the estate of a deceased loved one or we’ve created a will for ourselves. When the deceased leaves a will behind, it’s usually far easier to distribute his or her assets according to his or her wishes, which should be outlined in the will.

The will is a formal contract, but there is obviously one party who is doing all the giving and the others are simply the beneficiaries.

The concept of a final will and testament, then, conveys what seems to be the biblical reality of God’s covenant with man. God is infinitely greater, He’s the ultimate giver, and man is merely the beneficiary. And that’s why Melito wasn’t alone in noticing that the word testament (or diathākā) fits the biblical relationship between God and man slightly better than the word covenant (or synthākā).

About 500 years before Melito, and almost 300 years before the birth of Jesus, 70 translators got together to translate the Hebrew Scriptures into Greek (this is called the Septuagint, because of the 70 translators involved), and they used the word diathākā to translate the Hebrew word for covenant because they also understood that God and man are not equal parties.

And around 400 AD, Jerome published his Latin translation of the Old and New Testaments (called the Latin Vulgate, because vulgate or vulgar refers to something common). He followed the lead of those Greek translators of the Septuagint. Jerome called the Old Testament the Vetus Testamentum (Latin for Old Testament).

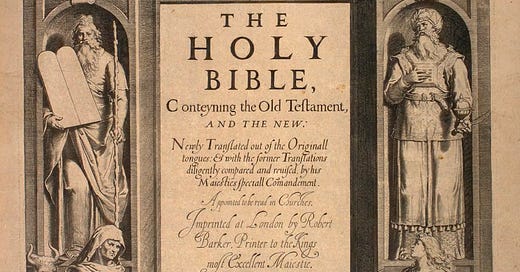

Of course, all English translations have followed the Greek and Latin titles, and that’s why we call them the Old and New Testaments today, and not the Old and New Covenants. It is interesting to note, however, that the English translations most frequently use the word covenant in the Scripture text itself.[2] You won’t find the word “testament” in the biblical text of most English Bible translations. The modern King James Version used it 14 times (though the 1611 translators seem to have preferred the word “couenant” to “teftament” in their translation), and the New King James Version reduced that number to 3.

The division of the Bible into the Old and New Testaments is evidence that God is a covenant-making and covenant-keeping God. God has made several covenants throughout history, some with a more narrow aperture (i.e., the ethnic people of ancient Israel) and some with a universal focus (i.e., all humanity). It is this covenantal progression and culmination (i.e., old to new) that many Christians have found to be a kind of framework to understand the whole storyline of the Bible.

If you’re interested in learning more about covenantal frameworks of the Bible and the various ways that Christians have perceived them, then I highly recommend a book by Benjamin Merkle - Discontinuity to Continuity: A Survey of Dispensational and Covenantal Theologies.

[1] See Eusebius’s account of Melito’s list in point #14 of this article. Also, note that Nehemiah was counted along with Ezra (aka “Esdras”) and Lamentations was counted along with Jeremiah. https://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf201.iii.ix.xxvi.html#fnf_iii.ix.xxvi-p59.2

[2] https://standingonshoulders.wordpress.com/2009/05/31/where-did-the-term-old-testament-and-new-testament-come-from/